cisatracurium besylate Clinical Pharmacology

()

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Cisatracurium besylate binds competitively to cholinergic receptors on the motor end-plate to antagonize the action of acetylcholine, resulting in blockade of neuromuscular transmission. This action is antagonized by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

The average ED95 (dose required to produce 95% suppression of the adductor pollicis muscle twitch response to ulnar nerve stimulation) of cisatracurium is 0.05 mg/kg (range: 0.048 to 0.053) in adults receiving opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

The pharmacodynamics of various cisatracurium doses administered over 5 to 10 seconds during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia are summarized in Table 5. When the cisatracurium dose is doubled, the clinically effective duration of blockade increases by approximately 25 minutes. Once recovery begins, the rate of recovery is independent of dose.

Isoflurane or enflurane administered with nitrous oxide/oxygen to achieve 1.25 MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration) prolonged the clinically effective duration of action of initial and maintenance cisatracurium doses, and decreased the average infusion rate requirement of cisatracurium besylate. The magnitude of these effects depended on the duration of administration of the volatile agents:

- •

- Fifteen to 30 minutes of exposure to 1.25 MAC isoflurane or enflurane had minimal effects on the duration of action of initial doses of cisatracurium besylate.

- •

- In surgical procedures during enflurane or isoflurane anesthesia greater than 30 minutes, less frequent maintenance dosing, lower maintenance doses, or reduced infusion rates of cisatracurium besylate were required. The average infusion rate requirement was decreased by as much as 30% to 40% [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

The onset, duration of action, and recovery profiles of cisatracurium besylate during propofol/oxygen or propofol/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia were similar to those during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia (see Table 5).

Repeated administration of maintenance cisatracurium besylate doses or a continuous cisatracurium besylate infusion for up to 3 hours was not associated with development of tachyphylaxis or cumulative neuromuscular blocking effects. The time needed to recover from successive maintenance doses did not change with the number of doses administered when partial recovery occurred between doses. The rate of spontaneous recovery of neuromuscular function after cisatracurium besylate infusion was independent of the duration of infusion and comparable to the rate of recovery following initial doses (see Table 5).

Pediatric patients including infants generally had a shorter time to maximum neuromuscular blockade and a faster recovery from neuromuscular blockade compared to adults treated with the same weight-based doses (see Table 5).

| Cisatracurium Besylate Dose | Time to 90% Block in minutes | Time to Maximum Block in minutes | 5% Recovery in minutes | 25% Recovery† in minutes | 95% Recovery in minutes | T4:T1 Ratio‡ ≥70% in minutes | 25%–75% Recovery Index in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

Adults | |||||||

0.1 mg/kg | 3.3 | 5 | 33 | 42 | 64 | 64 | 13 |

0.15¶mg/kg | 2.6 | 3.5 | 46 | 55 | 76 | 75 | 13 |

0.2 mg/kg | 2.4 | 2.9 | 59 | 65 | 81 | 85 | 12 |

0.25 mg/kg | 1.6 | 2 | 70 | 78 | 91 | 97 | 8 |

0.4 mg/kg | 1.5 | 1.9 | 83 | 91 | 121 | 126 | 14 |

Infants (1–23 months of age) | |||||||

0.15 mg/kg # | 1.5 | 2 | 36 | 43 | 64 | 59 | 11.3 |

Pediatric Patients (2–12 years) | |||||||

0.08 mg/kg Þ | 2.2 | 3.3 | 22 | 29 | 52 | 50 | 11 |

0.1 mg/kg | 1.7 | 2.8 | 21 | 28 | 46 | 44 | 10 |

0.15 mg/kg # | 2.1 | 3 | 29 | 36 | 55 | 54 | 10.6 |

Hemodynamics Profile

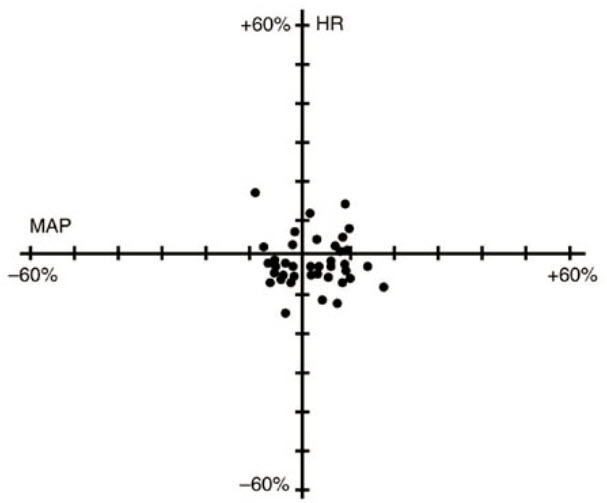

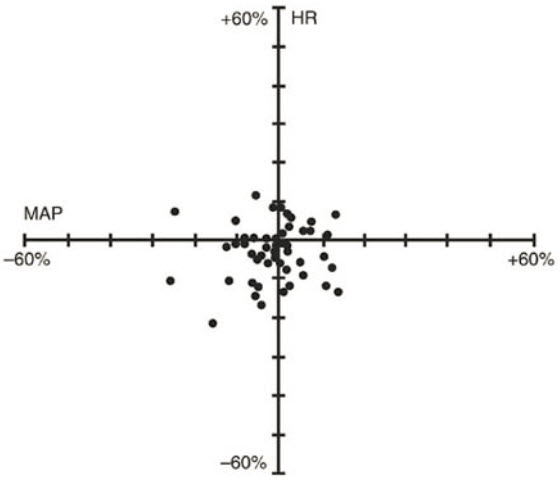

Cisatracurium Besylate Injection had no dose-related effects on mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) or heart rate (HR) following doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg, administered over 5 to 10 seconds, in healthy adult patients (see Figure 1) or in patients with serious cardiovascular disease (see Figure 2).

A total of 141 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery were administered cisatracurium besylate in three active-controlled clinical trials and received doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg. While the hemodynamic profile was comparable in both the cisatracurium besylate and active control groups, data for doses above 0.3 mg/kg in this population are limited.

Figure 1. Maximum Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP During First 5 Minutes after Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Doses in Healthy Adults Who Received Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia (n = 44)

Figure 2. Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP 10 Minutes After an Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Dose in Patients Undergoing CABG Surgery Receiving Oxygen/Fentanyl/Midazolam/Anesthesia (n = 54)

No clinically significant changes in MAP or HR were observed following administration of doses up to 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate over 5 to 10 seconds in 2- to 12-year-old pediatric patients who received either halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen or opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia. Doses of 0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate administered over 5 seconds were not consistently associated with changes in HR and MAP in pediatric patients aged 1 month to 12 years who received opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen or halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The neuromuscular blocking activity of cisatracurium besylate is due to parent drug. Cisatracurium plasma concentration-time data following IV bolus administration are best described by a two-compartment open model (with elimination from both compartments) with an elimination half-life (t½β) of 22 minutes, a plasma clearance (CL) of 4.57 mL/min/kg, and a volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) of 145 mL/kg.

Results from population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses from 241 healthy surgical patients are summarized in Table 6.

| Parameter | Estimate† | Magnitude of Interpatient Variability (CV)‡ |

|---|---|---|

| ||

CL (mL/min/kg) | 4.57 | 16% |

Vss (mL/kg)§ | 145 | 27% |

Keo (min-1)¶ | 0.0575 | 61% |

EC50 (ng/mL)# | 141 | 52% |

The magnitude of interpatient variability in CL was low (16%), as expected based on the importance of Hofmann elimination. The magnitudes of interpatient variability in CL and volume of distribution were low in comparison to those for keo and EC50. This suggests that any alterations in the time course of cisatracurium besylate-induced neuromuscular blockade were more likely to be due to variability in the PD parameters than in the PK parameters. Parameter estimates from the population PK analyses were supported by noncompartmental PK analyses on data from healthy patients and from specific populations.

Conventional PK analyses have shown that the PK of cisatracurium are proportional to dose between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.2 (4 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium. In addition, population PK analyses revealed no statistically significant effect of initial dose on CL for doses between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.4 (8 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium.

Distribution

The volume of distribution of cisatracurium is limited by its large molecular weight and high polarity. The Vss was equal to 145 mL/kg (Table 6) in healthy 19- to 64-year-old surgical patients receiving opioid anesthesia. The Vss was 21% larger in similar patients receiving inhalation anesthesia.

The binding of cisatracurium to plasma proteins has not been successfully studied due to its rapid degradation at physiologic pH. Inhibition of degradation requires nonphysiological conditions of temperature and pH which are associated with changes in protein binding.

Elimination

Organ-independent Hofmann elimination (a chemical process dependent on pH and temperature) is the predominant pathway for the elimination of cisatracurium. The liver and kidney play a minor role in the elimination of cisatracurium but are primary pathways for the elimination of metabolites. Therefore, the t½β values of metabolites (including laudanosine) are longer in patients with renal or hepatic impairment and metabolite concentrations may be higher after long-term administration [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

The mean CL values for cisatracurium ranged from 4.5 to 5.7 mL/min/kg in studies of healthy surgical patients. The compartmental PK modeling suggests that approximately 80% of the cisatracurium CL is accounted for by Hofmann elimination and the remaining 20% by renal and hepatic elimination. These findings are consistent with the low magnitude of interpatient variability in CL (16%) estimated as part of the population PK/PD analyses and with the recovery of parent and metabolites in urine.

In studies of healthy surgical patients, mean t½β values of cisatracurium ranged from 22 to 29 minutes and were consistent with the t½β of cisatracurium in vitro (29 minutes). The mean ± SD t½β values of laudanosine were 3.1 ± 0.4 hours in healthy surgical patients receiving cisatracurium besylate (n = 10).

Metabolism:

The degradation of cisatracurium was largely independent of liver metabolism. Results from in vitro experiments suggest that cisatracurium undergoes Hofmann elimination (a pH and temperature-dependent chemical process) to form laudanosine [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] and the monoquaternary acrylate metabolite, neither of which has any neuromuscular blocking activity. The monoquaternary acrylate undergoes hydrolysis by non-specific plasma esterases to form the monoquaternary alcohol (MQA) metabolite. The MQA metabolite can also undergo Hofmann elimination but at a much slower rate than cisatracurium. Laudanosine is further metabolized to desmethyl metabolites which are conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted in the urine.

The laudanosine metabolite of cisatracurium has been noted to cause transient hypotension and, in higher doses, cerebral excitatory effects when administered to several animal species. The relationship between CNS excitation and laudanosine concentrations in humans has not been established [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

During IV infusions of cisatracurium besylate, peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of laudanosine and the MQA metabolite were approximately 6% and 11% of the parent compound, respectively. The Cmax values of laudanosine in healthy surgical patients receiving infusions of cisatracurium besylate were mean ± SD Cmax: 60 ± 52 ng/mL.

Excretion:

Following 14C-cisatracurium administration to 6 healthy male patients, 95% of the dose was recovered in the urine (mostly as conjugated metabolites) and 4% in the feces; less than 10% of the dose was excreted as unchanged parent drug in the urine. In 12 healthy surgical patients receiving non-radiolabeled cisatracurium who had Foley catheters placed for surgical management, approximately 15% of the dose was excreted unchanged in the urine.

Special Populations

Geriatric Patients

The results of conventional PK analysis from a study of 12 healthy elderly patients and 12 healthy young adult patients who received a single IV cisatracurium besylate dose of 0.1 mg/kg are summarized in Table 7. Plasma clearances of cisatracurium were not affected by age; however, the volumes of distribution were slightly larger in elderly patients than in young patients resulting in slightly longer t½β values for cisatracurium.

The rate of equilibration between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade was slower in elderly patients than in young patients (mean ± SD keo: 0.071 ± 0.036 and 0.105 ± 0.021 minutes-1, respectively); there was no difference in the patient sensitivity to cisatracurium-induced block, as indicated by EC50 values (mean ± SD EC50: 91 ± 22 and 89 ± 23 ng/mL, respectively). These changes were consistent with the 1-minute slower times to maximum block in elderly patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate, when compared to young patients receiving the same dose. The minor differences in PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium between elderly patients and young patients were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

| Parameter | Healthy Elderly Patients | Healthy Young Adult Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 25.8 ± 3.6† | 22.1 ± 2.5 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State‡ (mL/kg) | 156 ± 17† | 133 ± 15 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 5.7 ± 1 | 5.3 ± 0.9 |

Patients with Hepatic Impairment:

Table 8 summarizes the conventional PK analysis from a study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation and 11 healthy adult patients undergoing elective surgery. The slightly larger volumes of distribution in liver transplant patients were associated with slightly higher plasma clearances of cisatracurium. The parallel changes in these parameters resulted in no difference in t½β values. There were no differences in keo or EC50 between patient groups. The times to maximum neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute faster in liver transplant patients than in healthy adult patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. These minor PK differences were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with hepatic disease and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

| Parameter | Liver Transplant Patients | Healthy Adult Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 24.4 ± 2.9 | 23.5 ± 3.5 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State† (mL/kg) | 195 ± 38‡ | 161 ± 23 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 6.6 ± 1.1‡ | 5.7 ± 0.8 |

Patients with Renal Impairment: Results from a conventional PK study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 healthy adult patients and 15 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who had elective surgery are summarized in Table 9. The PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were similar in healthy adult patients and ESRD patients. The times to 90% neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute slower in ESRD patients following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There were no differences in the durations or rates of recovery of cisatracurium besylate between ESRD and healthy adult patients.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with ESRD and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

Population PK analyses showed that patients with creatinine clearances ≤ 70 mL/min had a slower rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular block than patients with normal renal function; this change was associated with a slightly slower (~ 40 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients with renal impairment following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There was no clinically significant alteration in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate in patients with renal impairment. The recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate is unchanged in the presence of renal or hepatic failure, which is consistent with predominantly organ-independent elimination.

| Parameter | Healthy Adult Patients | ESRD Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 29.4 ± 4.1 | 32.3 ± 6.3 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State† (mL/kg) | 149 ± 35 | 160 ± 32 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 4.66 ± 0.86 | 4.26 ± 0.62 |

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients:

The PK of cisatracurium and its metabolites were determined in six ICU patients who received cisatracurium besylate and are presented in Table 10. The relationships between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade have not been evaluated in ICU patients.

Limited PK data are available for ICU patients with hepatic or renal impairment who received cisatracurium besylate. Relative to cisatracurium besylate -treated ICU patients with normal renal and hepatic function, metabolite concentrations (plasma and tissues) may be higher in cisatracurium besylate-treated ICU patients with renal or hepatic impairment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

| Parameter | Cisatracurium (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

Parent Compound | CL (mL/min/kg) | 7.45 ± 1.02 |

Laudanosine | Cmax (ng/mL) | 707 ± 360 |

MQA metabolite | Cmax (ng/mL) | |

Pediatric Population: The population PK/PD of cisatracurium were described in 20 healthy pediatric patients ages 2 to 12 years during halothane anesthesia, using the same model developed for healthy adult patients. The CL was higher in healthy pediatric patients (5.89 mL/min/kg) than in healthy adult patients (4.57 mL/min/kg) during opioid anesthesia. The rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular blockade, as indicated by keo, was faster in healthy pediatric patients receiving halothane anesthesia (0.1330 minutes-1) than in healthy adult patients receiving opioid anesthesia (0.0575 minutes-1). The EC50 in healthy pediatric patients (125 ng/mL) was similar to the value in healthy adult patients (141 ng/mL) during opioid anesthesia. The minor differences in the PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were associated with a faster time to onset and a shorter duration of cisatracurium-induced neuromuscular blockade in pediatric patients.

Sex and Obesity:

Although population PK/PD analyses revealed that sex and obesity were associated with effects on the PK and/or PD of cisatracurium; these PK/PD changes were not associated with clinically significant alterations in the predicted onset or recovery profile of Cisatracurium Besylate Injection.

Use of Inhalation Agents:

The use of inhalation agents was associated with a 21% larger Vss, a 78% larger keo, and a 15% lower EC50 for cisatracurium. These changes resulted in a slightly faster (~ 45 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients who received 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium during inhalation anesthesia than in patients who received the same dose of cisatracurium during opioid anesthesia; however, there were no clinically significant differences in the predicted recovery profile of Cisatracurium Besylate Injection between patient groups.

Drug Interaction Studies

Carbamazepine and phenytoin:

The systemic clearance of cisatracurium was higher in patients who were on prior chronic anticonvulsant therapy of carbamazepine or phenytoin [see Warning and Precautions (5.9) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Find cisatracurium besylate medical information:

Find cisatracurium besylate medical information:

cisatracurium besylate Quick Finder

Health Professional Information

Clinical Pharmacology

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Cisatracurium besylate binds competitively to cholinergic receptors on the motor end-plate to antagonize the action of acetylcholine, resulting in blockade of neuromuscular transmission. This action is antagonized by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

The average ED95 (dose required to produce 95% suppression of the adductor pollicis muscle twitch response to ulnar nerve stimulation) of cisatracurium is 0.05 mg/kg (range: 0.048 to 0.053) in adults receiving opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

The pharmacodynamics of various cisatracurium doses administered over 5 to 10 seconds during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia are summarized in Table 5. When the cisatracurium dose is doubled, the clinically effective duration of blockade increases by approximately 25 minutes. Once recovery begins, the rate of recovery is independent of dose.

Isoflurane or enflurane administered with nitrous oxide/oxygen to achieve 1.25 MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration) prolonged the clinically effective duration of action of initial and maintenance cisatracurium doses, and decreased the average infusion rate requirement of cisatracurium besylate. The magnitude of these effects depended on the duration of administration of the volatile agents:

- •

- Fifteen to 30 minutes of exposure to 1.25 MAC isoflurane or enflurane had minimal effects on the duration of action of initial doses of cisatracurium besylate.

- •

- In surgical procedures during enflurane or isoflurane anesthesia greater than 30 minutes, less frequent maintenance dosing, lower maintenance doses, or reduced infusion rates of cisatracurium besylate were required. The average infusion rate requirement was decreased by as much as 30% to 40% [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

The onset, duration of action, and recovery profiles of cisatracurium besylate during propofol/oxygen or propofol/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia were similar to those during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia (see Table 5).

Repeated administration of maintenance cisatracurium besylate doses or a continuous cisatracurium besylate infusion for up to 3 hours was not associated with development of tachyphylaxis or cumulative neuromuscular blocking effects. The time needed to recover from successive maintenance doses did not change with the number of doses administered when partial recovery occurred between doses. The rate of spontaneous recovery of neuromuscular function after cisatracurium besylate infusion was independent of the duration of infusion and comparable to the rate of recovery following initial doses (see Table 5).

Pediatric patients including infants generally had a shorter time to maximum neuromuscular blockade and a faster recovery from neuromuscular blockade compared to adults treated with the same weight-based doses (see Table 5).

| Cisatracurium Besylate Dose | Time to 90% Block in minutes | Time to Maximum Block in minutes | 5% Recovery in minutes | 25% Recovery† in minutes | 95% Recovery in minutes | T4:T1 Ratio‡ ≥70% in minutes | 25%–75% Recovery Index in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

Adults | |||||||

0.1 mg/kg | 3.3 | 5 | 33 | 42 | 64 | 64 | 13 |

0.15¶mg/kg | 2.6 | 3.5 | 46 | 55 | 76 | 75 | 13 |

0.2 mg/kg | 2.4 | 2.9 | 59 | 65 | 81 | 85 | 12 |

0.25 mg/kg | 1.6 | 2 | 70 | 78 | 91 | 97 | 8 |

0.4 mg/kg | 1.5 | 1.9 | 83 | 91 | 121 | 126 | 14 |

Infants (1–23 months of age) | |||||||

0.15 mg/kg # | 1.5 | 2 | 36 | 43 | 64 | 59 | 11.3 |

Pediatric Patients (2–12 years) | |||||||

0.08 mg/kg Þ | 2.2 | 3.3 | 22 | 29 | 52 | 50 | 11 |

0.1 mg/kg | 1.7 | 2.8 | 21 | 28 | 46 | 44 | 10 |

0.15 mg/kg # | 2.1 | 3 | 29 | 36 | 55 | 54 | 10.6 |

Hemodynamics Profile

Cisatracurium Besylate Injection had no dose-related effects on mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) or heart rate (HR) following doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg, administered over 5 to 10 seconds, in healthy adult patients (see Figure 1) or in patients with serious cardiovascular disease (see Figure 2).

A total of 141 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery were administered cisatracurium besylate in three active-controlled clinical trials and received doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg. While the hemodynamic profile was comparable in both the cisatracurium besylate and active control groups, data for doses above 0.3 mg/kg in this population are limited.

Figure 1. Maximum Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP During First 5 Minutes after Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Doses in Healthy Adults Who Received Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia (n = 44)

Figure 2. Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP 10 Minutes After an Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Dose in Patients Undergoing CABG Surgery Receiving Oxygen/Fentanyl/Midazolam/Anesthesia (n = 54)

No clinically significant changes in MAP or HR were observed following administration of doses up to 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate over 5 to 10 seconds in 2- to 12-year-old pediatric patients who received either halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen or opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia. Doses of 0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate administered over 5 seconds were not consistently associated with changes in HR and MAP in pediatric patients aged 1 month to 12 years who received opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen or halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The neuromuscular blocking activity of cisatracurium besylate is due to parent drug. Cisatracurium plasma concentration-time data following IV bolus administration are best described by a two-compartment open model (with elimination from both compartments) with an elimination half-life (t½β) of 22 minutes, a plasma clearance (CL) of 4.57 mL/min/kg, and a volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) of 145 mL/kg.

Results from population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses from 241 healthy surgical patients are summarized in Table 6.

| Parameter | Estimate† | Magnitude of Interpatient Variability (CV)‡ |

|---|---|---|

| ||

CL (mL/min/kg) | 4.57 | 16% |

Vss (mL/kg)§ | 145 | 27% |

Keo (min-1)¶ | 0.0575 | 61% |

EC50 (ng/mL)# | 141 | 52% |

The magnitude of interpatient variability in CL was low (16%), as expected based on the importance of Hofmann elimination. The magnitudes of interpatient variability in CL and volume of distribution were low in comparison to those for keo and EC50. This suggests that any alterations in the time course of cisatracurium besylate-induced neuromuscular blockade were more likely to be due to variability in the PD parameters than in the PK parameters. Parameter estimates from the population PK analyses were supported by noncompartmental PK analyses on data from healthy patients and from specific populations.

Conventional PK analyses have shown that the PK of cisatracurium are proportional to dose between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.2 (4 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium. In addition, population PK analyses revealed no statistically significant effect of initial dose on CL for doses between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.4 (8 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium.

Distribution

The volume of distribution of cisatracurium is limited by its large molecular weight and high polarity. The Vss was equal to 145 mL/kg (Table 6) in healthy 19- to 64-year-old surgical patients receiving opioid anesthesia. The Vss was 21% larger in similar patients receiving inhalation anesthesia.

The binding of cisatracurium to plasma proteins has not been successfully studied due to its rapid degradation at physiologic pH. Inhibition of degradation requires nonphysiological conditions of temperature and pH which are associated with changes in protein binding.

Elimination

Organ-independent Hofmann elimination (a chemical process dependent on pH and temperature) is the predominant pathway for the elimination of cisatracurium. The liver and kidney play a minor role in the elimination of cisatracurium but are primary pathways for the elimination of metabolites. Therefore, the t½β values of metabolites (including laudanosine) are longer in patients with renal or hepatic impairment and metabolite concentrations may be higher after long-term administration [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

The mean CL values for cisatracurium ranged from 4.5 to 5.7 mL/min/kg in studies of healthy surgical patients. The compartmental PK modeling suggests that approximately 80% of the cisatracurium CL is accounted for by Hofmann elimination and the remaining 20% by renal and hepatic elimination. These findings are consistent with the low magnitude of interpatient variability in CL (16%) estimated as part of the population PK/PD analyses and with the recovery of parent and metabolites in urine.

In studies of healthy surgical patients, mean t½β values of cisatracurium ranged from 22 to 29 minutes and were consistent with the t½β of cisatracurium in vitro (29 minutes). The mean ± SD t½β values of laudanosine were 3.1 ± 0.4 hours in healthy surgical patients receiving cisatracurium besylate (n = 10).

Metabolism:

The degradation of cisatracurium was largely independent of liver metabolism. Results from in vitro experiments suggest that cisatracurium undergoes Hofmann elimination (a pH and temperature-dependent chemical process) to form laudanosine [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] and the monoquaternary acrylate metabolite, neither of which has any neuromuscular blocking activity. The monoquaternary acrylate undergoes hydrolysis by non-specific plasma esterases to form the monoquaternary alcohol (MQA) metabolite. The MQA metabolite can also undergo Hofmann elimination but at a much slower rate than cisatracurium. Laudanosine is further metabolized to desmethyl metabolites which are conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted in the urine.

The laudanosine metabolite of cisatracurium has been noted to cause transient hypotension and, in higher doses, cerebral excitatory effects when administered to several animal species. The relationship between CNS excitation and laudanosine concentrations in humans has not been established [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

During IV infusions of cisatracurium besylate, peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of laudanosine and the MQA metabolite were approximately 6% and 11% of the parent compound, respectively. The Cmax values of laudanosine in healthy surgical patients receiving infusions of cisatracurium besylate were mean ± SD Cmax: 60 ± 52 ng/mL.

Excretion:

Following 14C-cisatracurium administration to 6 healthy male patients, 95% of the dose was recovered in the urine (mostly as conjugated metabolites) and 4% in the feces; less than 10% of the dose was excreted as unchanged parent drug in the urine. In 12 healthy surgical patients receiving non-radiolabeled cisatracurium who had Foley catheters placed for surgical management, approximately 15% of the dose was excreted unchanged in the urine.

Special Populations

Geriatric Patients

The results of conventional PK analysis from a study of 12 healthy elderly patients and 12 healthy young adult patients who received a single IV cisatracurium besylate dose of 0.1 mg/kg are summarized in Table 7. Plasma clearances of cisatracurium were not affected by age; however, the volumes of distribution were slightly larger in elderly patients than in young patients resulting in slightly longer t½β values for cisatracurium.

The rate of equilibration between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade was slower in elderly patients than in young patients (mean ± SD keo: 0.071 ± 0.036 and 0.105 ± 0.021 minutes-1, respectively); there was no difference in the patient sensitivity to cisatracurium-induced block, as indicated by EC50 values (mean ± SD EC50: 91 ± 22 and 89 ± 23 ng/mL, respectively). These changes were consistent with the 1-minute slower times to maximum block in elderly patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate, when compared to young patients receiving the same dose. The minor differences in PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium between elderly patients and young patients were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

| Parameter | Healthy Elderly Patients | Healthy Young Adult Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 25.8 ± 3.6† | 22.1 ± 2.5 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State‡ (mL/kg) | 156 ± 17† | 133 ± 15 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 5.7 ± 1 | 5.3 ± 0.9 |

Patients with Hepatic Impairment:

Table 8 summarizes the conventional PK analysis from a study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation and 11 healthy adult patients undergoing elective surgery. The slightly larger volumes of distribution in liver transplant patients were associated with slightly higher plasma clearances of cisatracurium. The parallel changes in these parameters resulted in no difference in t½β values. There were no differences in keo or EC50 between patient groups. The times to maximum neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute faster in liver transplant patients than in healthy adult patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. These minor PK differences were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with hepatic disease and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

| Parameter | Liver Transplant Patients | Healthy Adult Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 24.4 ± 2.9 | 23.5 ± 3.5 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State† (mL/kg) | 195 ± 38‡ | 161 ± 23 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 6.6 ± 1.1‡ | 5.7 ± 0.8 |

Patients with Renal Impairment: Results from a conventional PK study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 healthy adult patients and 15 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who had elective surgery are summarized in Table 9. The PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were similar in healthy adult patients and ESRD patients. The times to 90% neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute slower in ESRD patients following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There were no differences in the durations or rates of recovery of cisatracurium besylate between ESRD and healthy adult patients.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with ESRD and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

Population PK analyses showed that patients with creatinine clearances ≤ 70 mL/min had a slower rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular block than patients with normal renal function; this change was associated with a slightly slower (~ 40 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients with renal impairment following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There was no clinically significant alteration in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate in patients with renal impairment. The recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate is unchanged in the presence of renal or hepatic failure, which is consistent with predominantly organ-independent elimination.

| Parameter | Healthy Adult Patients | ESRD Patients |

|---|---|---|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) | 29.4 ± 4.1 | 32.3 ± 6.3 |

Volume of Distribution at Steady State† (mL/kg) | 149 ± 35 | 160 ± 32 |

Plasma Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 4.66 ± 0.86 | 4.26 ± 0.62 |

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients:

The PK of cisatracurium and its metabolites were determined in six ICU patients who received cisatracurium besylate and are presented in Table 10. The relationships between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade have not been evaluated in ICU patients.

Limited PK data are available for ICU patients with hepatic or renal impairment who received cisatracurium besylate. Relative to cisatracurium besylate -treated ICU patients with normal renal and hepatic function, metabolite concentrations (plasma and tissues) may be higher in cisatracurium besylate-treated ICU patients with renal or hepatic impairment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

| Parameter | Cisatracurium (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

Parent Compound | CL (mL/min/kg) | 7.45 ± 1.02 |

Laudanosine | Cmax (ng/mL) | 707 ± 360 |

MQA metabolite | Cmax (ng/mL) | |

Pediatric Population: The population PK/PD of cisatracurium were described in 20 healthy pediatric patients ages 2 to 12 years during halothane anesthesia, using the same model developed for healthy adult patients. The CL was higher in healthy pediatric patients (5.89 mL/min/kg) than in healthy adult patients (4.57 mL/min/kg) during opioid anesthesia. The rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular blockade, as indicated by keo, was faster in healthy pediatric patients receiving halothane anesthesia (0.1330 minutes-1) than in healthy adult patients receiving opioid anesthesia (0.0575 minutes-1). The EC50 in healthy pediatric patients (125 ng/mL) was similar to the value in healthy adult patients (141 ng/mL) during opioid anesthesia. The minor differences in the PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were associated with a faster time to onset and a shorter duration of cisatracurium-induced neuromuscular blockade in pediatric patients.

Sex and Obesity:

Although population PK/PD analyses revealed that sex and obesity were associated with effects on the PK and/or PD of cisatracurium; these PK/PD changes were not associated with clinically significant alterations in the predicted onset or recovery profile of Cisatracurium Besylate Injection.

Use of Inhalation Agents:

The use of inhalation agents was associated with a 21% larger Vss, a 78% larger keo, and a 15% lower EC50 for cisatracurium. These changes resulted in a slightly faster (~ 45 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients who received 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium during inhalation anesthesia than in patients who received the same dose of cisatracurium during opioid anesthesia; however, there were no clinically significant differences in the predicted recovery profile of Cisatracurium Besylate Injection between patient groups.

Drug Interaction Studies

Carbamazepine and phenytoin:

The systemic clearance of cisatracurium was higher in patients who were on prior chronic anticonvulsant therapy of carbamazepine or phenytoin [see Warning and Precautions (5.9) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Health Professional Information

{{section_name_patient}}

{{section_body_html_patient}}

Resources

Didn’t find what you were looking for? Contact us.

Chat online with Pfizer Medical Information regarding your inquiry on a Pfizer medicine.

*Speak with a Pfizer Medical Information Professional regarding your medical inquiry. Available 9AM-5Pm ET Monday to Friday; excluding holidays.

Submit a medical question for Pfizer prescription products.

Report Adverse Event

To report an adverse event related to the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine, and you are not part of a clinical trial* for this product, click the link below to submit your information:

Pfizer Safety Reporting Site*If you are involved in a clinical trial for this product, adverse events should be reported to your coordinating study site.

If you cannot use the above website, or would like to report an adverse event related to a different Pfizer product, please call Pfizer Safety at (800) 438-1985.

You may also contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) directly to report adverse events or product quality concerns either online at www.fda.gov/medwatch or call (800) 822-7967.